|

| The Aye-Aye. Not all lemurs are adorable. |

Douglas Adams is best known as the author of the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, which is a series of books (and many other media) that had a profound influence on my developing sense of humor as a goofy sixth grader. The idea that you could blend science fiction with Monty Python-esque humor blew my mind, particularly because I realized that a lot of it was clearly going right over my head. For example, as a twelve year old, I had no idea what bureaucracy was, nor how absurd and maddening it can be to navigate. But because it was a favorite topic of satire for Adams, it gave me an intriguing glimpse of my own future of tax returns, mortgage applications, and endless visits to the DMV.

|

| Mark Carwardine and Douglas Adams |

As much as I loved the fictional universe that Douglas Adams created, it is his writing about our own world that has continued to resonate with me. In 1985, a magazine editor had the bright idea of teaming Adams up with a photographer and a naturalist to attempt to spot an extremely rare and endangered lemur in the wild. I'll let Mr. Adams introduce the trip:

This isn't at all what I expected. In 1985, by some sort of journalistic accident, I was sent to Madagascar with Mark Carwardine to look for an almost extinct form of lemur called the aye-aye. None of the three of us had met before. I had never met Mark, Mark had never met me, and no one, apparently, had seen an aye-aye in years.

This was the idea of the Observer Colour Magazine, to throw us all in at the deep end. Mark is an extremely experienced and knowledgeable zoologist, working at that time for the World Wildlife Fund, and his role, essentially, was to be the one who knew what he was talking about. My role, and one for which I was entirely qualified, was to be an extremely ignorant non-zoologist to whom everything that happened would come as a complete surprise. All the aye-aye had to do was do what aye-ayes have been doing for millions of years - sit in a tree and hide.

|

| The aye-aye. |

Sadly, Douglas Adams died in 2001. However, his passion and advocacy inspired many, including his friend Stephen Fry. In 2009, the BBC aired a six part documentary series, in which Fry and Mark Carwardine retraced their journey, checking in to see how each species had fared over the decades.

By now, you're perhaps wondering if I'm ever going mention the fine students of Summers-Knoll, and what any of this has to do with them. I am, indeed!

We read the first chapter of Last Chance to See in class, which is a fun and useful primer for evolutionary biology, plate tectonics, ecology, conservation, and more. It's titled "Twig Technology," and I essentially want to quote the entire thing. Instead, here are three paragraphs that I have found delightfully concise and informative.

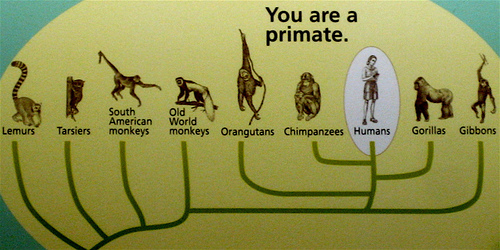

Like virtually everything that lives on Madagascar, [the aye aye] does not exist anywhere else on earth. Its origins date back to a period in earth's history when Madagascar was still part of mainland Africa (which itself had been part of the gigantic supercontinent of Gondwanaland), at which time the ancestors of the Madagascan lemurs were the dominant primate in all the world. When Madagascar sheered off into the Indian Ocean it became entirely isolated from all the evolutionary changes that took place in the rest of the world. It is a life raft from a different time. It is now almost like a tiny, fragile, separate planet.

The major evolutionary change which passed Madagascar by was the arrival of the monkeys. These were descended from the same ancestors as the lemurs, but they had bigger brains, and were aggressive competitors for the same habitat. Where the lemurs had been content to hang around in trees having a good time, the monkeys were ambitious, and interested in all sorts of things, especially twigs, with which they found they could do all kinds of things that they couldn't do by themselves - digging for things, probing things, hitting things. The monkeys took over the world and the lemur branch of the primate family died out everywhere - other than Madagascar, which for millions of years the monkeys never reached.

Then fifteen hundred years ago, the monkeys finally arrived, or at least, the monkey's descendants - us. Thanks to astounding advances in twig technology we arrived in canoes, then boats and finally aeroplanes, and once again started to compete for use of the same habitat, only this time with fire and machetes and domesticated animals, with asphalt and concrete. The lemurs are once again fighting for survival.

In just these three paragraphs, we found at least five different concepts to unpack and discuss. Later, after reading the entire chapter, we watched the episode of the 2009 BBC series that followed up their visit.

If you're interested, you can view it here:

While planning the book, Douglas Adams was able to tell Mark Carwardine where on the planet that he would like to visit, and Carwardine was easily able to find species there that were endangered and in dire need of publicity and help. Taking this as inspiration, we took stock of our own corner of the globe.

Each student read though this list of threatened or endangered species in the state of Michigan. Then, they selected one to learn about its situation. What is it? Why is it endangered? What is being done about it?

Having done research on their particular organism, each student is preparing a short (5-10 minute) presentation on what they learned. Some students gave their presentations to the assembled 5/6 classes over the week. The remaining presentations are forthcoming.

|

| Kaz discusses the Copperbelly water snake. |

|

| Henry teaches us about the Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake. |

|

| Oliver presenting on the Piping Plover. |

|

| Niko tells us about the Northern Long-Eared Bat. |

After sharing what we've learned about this sampling of endangered species, we'll look toward what active steps we can take to preserve these (and many other) species in our own communities.

|

| The highly-specialized hand of the aye-aye. |

No comments:

Post a Comment